Thoughts from Elizabeth Byers, author of Wildflowers of Mount Everest

I couldn’t help a swell of happiness as I got my first look at KEEP’s new handbook on Minimum Impact Travel, written by Amit Khadka. This handbook articulates so many feelings that I’ve struggled to express during my 45 years of trekking in Nepal. It is a comprehensive and important contribution to sustainable low-impact tourism in Nepal. It is also beautifully presented and highly readable. Congratulations to Amit Khadka and all of the good people who worked to create this valuable new resource for Nepal.

My husband Alton and I are now getting ready for our next trekking expedition to see the spectacular rhododendrons, primroses, and early monsoon flora of Kanchenjunga and Makalu. As we plan our trek, we’re also reflecting on many past trips and thinking about the importance of the guidelines of Minimum Impact Travel.

First, advance planning and preparation. I am a student of botany and vegetation ecology, so I like to trek during the growing season and monsoon, when there are no crowds. Getting to see the glorious flowering of the subalpine and alpine flora is worth every bit of dodging raindrops. It is also an incredible privilege to talk to local herders as they follow ancient patterns of migration to alpine pastures. This trek will have both lodge stays and tent camping. We’re lucky to have a trekking agency that cares about the environment, so we can relax about that part. We know that when we camp, we’ll be in established campsites or resilient pasture areas. We’ll have plenty of kerosene for the stoves, every campsite will be cleaned up completely, and all trash will be packed out with us. We’ll eat delicious packaging-free food: rice and lentils, potatoes, momos, chapattis, eggs, local greens, and tea for a beverage. Whenever we have new staff joining us, though, I feel it is my responsibility to ensure that they know how much I care (and will check) to be sure we are not cutting trees, picking or digging medicinal plants, leaving trash, or otherwise harming the environment.

When we stay in lodges, it will be easy to order tasty local dishes and beverages rather than the (sometimes ancient) canned or bottled goods on the shelves. My husband Alton is very interested in fuelwood and waste disposal, and often ends up talking at length to lodge owners about possible sustainable solutions for these challenges. We have been particularly alarmed by the build-up of large stacks of glass beer bottles along some trekking routes in Makalu and Kanchenjunga, and the general proliferation of broken glass, which is a tremendous hazard to wildlife and livestock.

I have a list of what to pack based on my many expeditions, so it only takes me a couple of hours to get everything ready. It is amazing how little you need to spend six weeks on the trail. Clothing is about function, not fashion, so a single change of base layer plus outer layers for warmth and good rain gear. Shoes are the bulkiest item, but the biggest pair, hiking boots, stay on my feet most of the time. I also bring camp slippers for warmth and flipflops for hot weather. Since I will need to pack out everything I bring in, I minimize wherever I can. Items like shampoo and conditioner now come in bar form, just like a small bar of soap, which means no spillage and no waste. I bring a small power pack and foldable solar panel to recharge my headlamp, e-reader, and camera. A good water filter is a must, since it means I can avoid all bottled and canned beverages. Everything goes into 2-gallon waterproof plastic bags, which come home with me to be used again on the next trek. As I get older, I find that I need trekking poles for the steep sections of the trail. I know they cause erosion, so I keep the rubber tips on and try to place the poles on rocks or roots, not on soft soil and especially not in mud. I have the folding style of poles so when I don’t need them, they can fold up into my pack.

I applaud the Minimum Impact Travel guidelines to trek mostly in high-use areas that already have good infrastructure and trails. These are also some of the most scenic areas, which is exactly why they have become popular. I have found that a peaceful crowd-free experience can be as simple as trekking in the off-season. For a person who loves plants, the monsoon is actually the best time to trek. However, I fall short on the guideline to trek in high-use areas as I have been recently trekking in more remote areas while working with three Nepali co-authors on a new book on the Flowers of Kanchenjunga Conservation Area. I’m aware that it is a responsibility when I am off the beaten track to have the least environmental impact possible, and also to be very conscious that I’m a visitor in someone else’s community, and act with utmost respect to the people I meet.

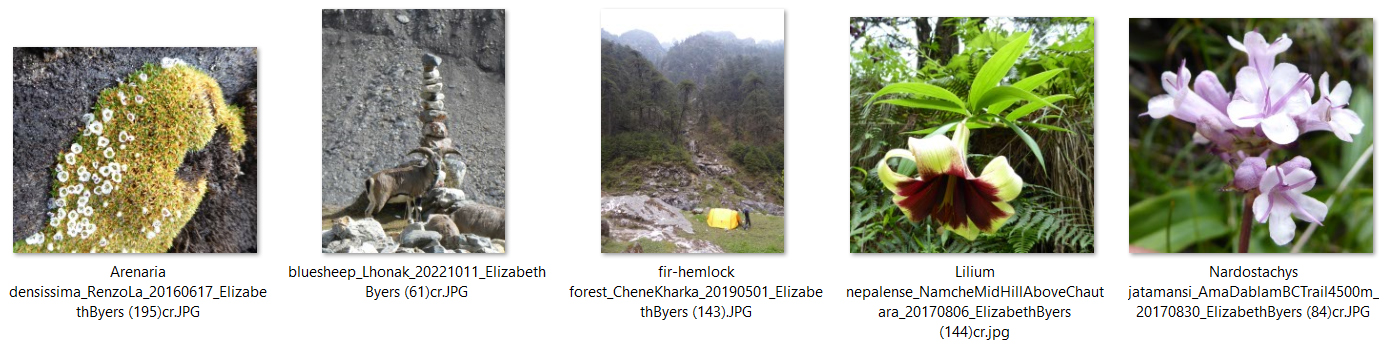

I do try to talk to other people about conservation when there is an opportunity. As a vegetation ecologist, sometimes I’m aware of the larger context for rare or threatened species that are also used locally. Many medicinal plants in Nepal are threatened by over-harvesting. Visitors to an area, including trekking staff or porters, should not pick or dig any plants at all. Local communities should be conscious of their impacts and aware of the laws protecting threatened species. Many species are fine to harvest for local use, but it is illegal to harvest them for commercial sale. Harvested species that might cross international borders are even more strictly protected. If a species is known to be legally harvestable, then a good rule of thumb for local communities is to harvest no more than 2% of the population, or one plant per 50 in a given population, and to harvest the minimal amount needed, planting back the seeds or roots whenever possible.

Once I’m on the trail, it is such a joy to soak in the peacefulness and beauty of the natural world, watching for wildlife and birds and feeling humbled by the vast landscapes. Every new plant that I get to see is a small miracle. I’m especially attracted to the extremophile plants that grow slowly on cliffs, in alpine areas, and even on top of the melting glaciers. Some of these plants are hundreds of years old and a single boot trample could damage them. I have found that a good optical zoom or tele-macro will allow me to photograph plants from a safe distance to avoid trampling sensitive habitats. On popular trails such as the Mount Everest Base Camp trail, nearly every plant in my mobile app “Wildflowers of Mount Everest” can be seen and photographed without stepping off the main trail. I think of the stone walls that line this trail as the hanging gardens of Khumbu, where beautiful flowers bloom right at eye level. Journaling, sketching, and photography are amazing ways to capture the natural beauty of Nepal with damaging it.

The new handbook for Minimal Impact Travel is a fabulous resource for anyone visiting Nepal or working in the tourism sector. For me, it was a great compilation of many issues I’ve been concerned about over the years and a reminder of the importance of paying close attention to my own impacts. The exceptional beauty of Nepal’s natural and cultural environments is at stake.

Photo captions:

Arenaria densissima (Tibetan: pangatong) is an alpine cushion plant that takes hundreds of years to grow to this size. It is threatened by overharvesting as a fuel source.

Blue sheep. The joys of sitting quietly – a flock of blue sheep wandered past our lodge at dusk, in Lhonak, Kanchenjunga Conservation Area.

Campsite at an established goTh (herder’s campsite) on resilient vegetation, with fir-hemlock forest in the background, at Chene Kharka in Kanchenjunga Conservation Area.

Lilium nepalense (Nepali: khiraunla) is a showy medicinal species that is threatened by overharvesting.

Nardostachys jatamansi (Nepali: jatamansi) is an important medicinal plant that is threatened by overharvesting.